- USMB FAMILY

- Who We Are

- Districts & Churches

- District Overview

- CHRISTIAN LEADER

- Title

- I said ‘Yes’ to God’s callA chocolate milkshake with my pastor, Al Kroeker, when I was in high school sparked 40 years of ministry. He suggested I’d make a good pastor. No thanks, I told him, I want to be a doctor. Upon reflection, this was an early lesson in ministry: Being a pastor isn’t about wanting to be a pastor; it’s about accepting God’s call. Over time, I did. Nothing but God’s call could ever sustain a pastor in ministry. I know. My calling to ministry, particularly as a local church pastor, was initiated and sustained by the encouragement and prayers of God’s people […]

- Made in the image of GodThey have Jesus this time. They know it too, as they rub their hands together gleefully. Off and on for three years the religious leaders have been trying to get him, to trap him into saying something that will either make his people reject him or the authorities arrest him. And now they have come up with the perfect question, a question that damns Jesus no matter how he answers it, a loaded question, one that will trap him either way. They approach him, albeit a bit apprehensively. They know Jesus is clever. But they are confident in their trap. […]

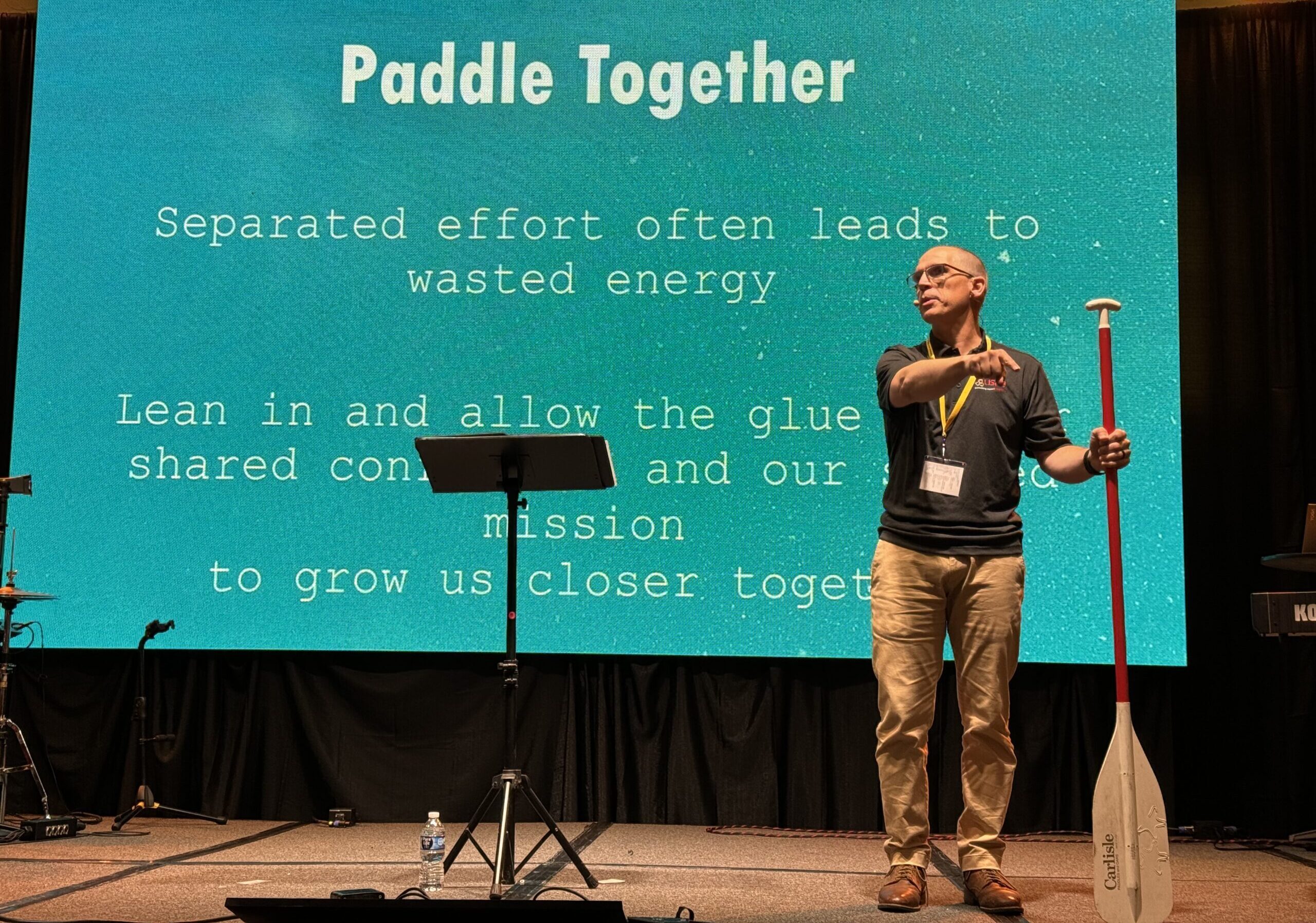

- Gathering 2024 highlights staff changesUSMB Gathering 2024, held July 23-27, in Omaha, Nebraska, marked transitions in national conference staff. Aaron Box, a USMB pastor from Eugene, Oregon, was introduced as the new national director while retiring national director Don Morris and USMB staff members Donna Sullivan and Lori Taylor were recognized for a combined six decades of service. Box, whose appointment as the lead national staff member was announced in May, addressed delegates Friday morning in a message that touched on the convention theme and outlined his vision for U.S. Mennonite Brethren. Saying that there can be no spectators as USMB moves forward, Box […]

- WHAT WE DO

- Church Multiplication

- Church planting continues to be a crucial area of ministry for USMB. Studies show churches are the most effective way to bring more people into the family of God. Partnering with local churches, districts, USMB and Multiply to plant churches, is not just a good thing to do, we must do it.Read More

- Disciple-Making

- USMB is actively involved in helping provide our churches with dynamic ideas, resources and programs for encouraging people to become fully-devoted followers of Jesus. Jesus said, “Go and make disciples….” We strive to facilitate that profound command. READ MORE about Disciple-making.Read More

- Leadership Development

- USMB’s leadership development strategy stems from the real need to actively develop more leaders within the local church who are living on mission in the workplace and in their communities and to fulfill the demand for additional pastors, church planters and missionaries. READ MORE about Leadership Development opportunities.Read More

- Leadership Development

- RESOURCES

- EVENTS

- CONTACT

- CHURCHES

- JOBS

- Disciple-Making

-

- Church Multiplication

Increasing Impact Together

T 800-257-0515

Email: offices@usmb.org

USMB

PO Box 20200 Wichita, KS 67208

PHONE: 800-257-0515 NEWSLETTER: SIGN UP

OUR STORY

For more information about this video on Mennonite Brethren history click HERE.

U.S. Mennonite Brethren have a rich spiritual heritage that can be traced back to the heart of the 16th century Reformation. From the start, our spiritual forefathers were determined to hold to the Bible as the non-negotiable source of truth and to pursue radical obedience to that truth.

Today we remain unswervingly committed to these aspirations, although we know we have not always lived up to them. We share this commitment with a global Mennonite Brethren family known as the International Community of Mennonite Brethren, a fellowship of 21 national conferences around the world with a total of about 450,000 members.

The following summary of Mennonite Brethren history is excerpted from Family Matters: Discovering the Mennonite Brethren by Lynn Jost and Connie Faber, published by Kindred Productions in 2002.

The Reformation

In the early 1500s Martin Luther, a German priest, began studying the Bible in a way that critiqued some of the problems in the established church. He became convinced that God offered the divine gift of righteousness to believers in God. When Luther was blocked in his efforts to reform the established church, he went public with 95 indictments of church abuses. His actions in 1517 started the Reformation movement that touched many countries and regions simultaneously in Europe.

In Switzerland, two other reformers reached similar conclusions. In Geneva, former lawyer John Calvin reacted much the same way as Luther. In Zurich, Ulrich Zwingli also preached reform. Known as “the People’s Priest,” Zwingli was flamboyant, energetic and a powerful preacher.

The Radical Reformation — Anabaptists

Zwingli attracted a group of young radicals who wanted even more reform. Conrad Grebel was a bright but rebellious son of high society. His decadent life had been transformed through new birth in Christ.

Zwingli’s colleague, Felix Manz, and Grebel disagreed with Zwingli on the issue of baptism, arguing for believers’ baptism rather than infant baptism. They also advocated the separation of church and state.

The Zurich Council ordered Grebel and Manz to stop their home Bible studies, and so the group broke completely with the established church. This group met January 21, 1525 to pray about their critical situation. Moved by the Spirit and with great fear, every person present was baptized and pledged to live in separation from the world. Anabaptism — to be baptized again — was born.

The Mennonites

Because of the break with the established church, the Anabaptists experienced persecution and martyrdom. Many fled from Switzerland to various places in Europe, including Holland where former Catholic priest Menno Simons lived.

Initially, Menno was a typical priest of the time. He performed the formal religious rituals but otherwise occupied himself with frivolous activity and maintained a low spiritual vitality. But Menno was having serious personal doubts about some aspects of his religious tradition. Then he heard the news about a simple tailor who had been beheaded for his rebaptism.

Menno turned to the New Testament and concluded that infant baptism had no Scriptural basis and advocated adult baptism upon confession of faith. At this point, in 1531, Menno was convinced that the Anabaptists were correct regarding three truths:

- that the Bible, not church tradition, was the authority in matters of faith;

- that the Lord’s Supper was a memorial commemorating Christ’s redemptive act, not a sacrifice of his flesh and blood; and

- that baptism was an act of faithful adult discipleship, not a christening event to make children Christians.

Menno remained in the Catholic church for a few more years. Then his brother was killed in a revolutionary battle for an error in teaching that developed in a segment of the Anabaptist movement, and Menno felt that he should have taught more openly — that perhaps it might have prevented this disaster.

So, Menno went public with his convictions, was rebaptized and in 1537 officially joined the Anabaptist movement. He became the overseer of several congregations in Holland and Germany. He traveled constantly, partly to encourage people in the movement and partly to stay ahead of his persecutors. By 1542 the price of 100 gold guilders was placed on Menno’s head.

The Mennonite Church bears his name not because Menno was the founder but because he was a church leader who rallied a scattered people and led them through a time of great tribulation. He wrote over two dozen books and pamphlets — on the run —and defined the theology which was to become the Mennonite church. He placed 1 Corinthians 3:11 on the title page of all his writings: “For no one can lay any foundation other than the one already laid, which is Jesus Christ.”

Interestingly, in 1561 Menno Simons died peacefully in Denmark.

Migration to Poland

In the mid-1500s persecution and evangelistic impulses pushed the frontier of the Mennonite church from Holland to the Vistula Delta of Poland near Danzig. Polish nobles welcomed the newcomers to their estates as farm laborers. The Mennonite immigrants drained swampy lowlands, built farms and, despite restrictions, established churches. For 250 years (1540–1790), Mennonites lived in religious and cultural isolation. They developed a lifestyle of religious tradition and cultural conservatism. Lack of missionary vision caused them to be known as “The Quiet in the Land.”

The area came under Prussian rule in 1772. The pressure of Prussian militarism under Frederich the Great made it increasingly difficult for the non-resistant Mennonites. Their’ refusal to pay taxes to support the state church and the military establishment together, with government restrictions on the purchase of more land for their growing families, forced the Mennonites to look for a new home.

Mennonite Colonies in Russia

Many Prussian Mennonites saw the land settlement policy announced in 1763 by Catherine the Great of Russia as providential. Russia was looking for industrious settlers for new territories acquired north of the Black Sea. Mennonites and other German immigrants were promised freedom of faith, nonparticipation in the military, land ownership and self-government.

Starting in 1788, the Mennonites established German-speaking colonies of small villages with farmlands, church buildings, schools and homes. The early years on the Ukrainian steppes were difficult, but the industrious Mennonites eventually established themselves and by 1860 reached a population of 30,000.

Ironically, by the mid 1800s the Russian Mennonite church had taken on many of the characteristics of the European state church of the 1500s. Church membership was a prerequisite for civic privileges such as voting, land ownership and marriage. Baptism was extended to those who completed a catechism class without insistence on personal commitment to Jesus Christ.

Church elders began to act as civic authorities and many showed no evidence of discipleship themselves. Church discipline, pastoral counseling and mutual care were often neglected. Divisions between wealthy members and the impoverished landless class deepened. Public drunkenness, gambling and moral decadence went undisciplined. The ordinances of the Lord’s Supper and baptism took on a sacramental character, a sense that the rite itself replaced a need for disciplined Christian living. The Russian Mennonites faced social, economic, intellectual and spiritual stagnation. They were in need of renewal.

Revival Movements

Eduard Wuest, a Lutheran Pietist pastor, was the greatest catalyst for renewal among Russian Mennonites in the mid-19th century. After a personal conversion experience, he developed into a powerful preacher. Gifted with a commanding physique, melodious voice and attractive personality, Wuest was frequently a guest speaker in Mennonite churches. Many who were weary of lifeless formalism were drawn by his message into a vibrant spiritual relationship with God and each other.

A clash between Wuest’s followers and the established Mennonite Church seemed inevitable, but before the renewal could organize into a formal movement Wuest himself died in 1859 at the age of 42. Wuest was an important catalyst, but with his death the renewal movement turned to its Anabaptist roots for a New Testament concept of church.

Birth of the Mennonite Brethren

Many people had been converted to personal faith in Jesus in several villages of the Molotschna Mennonite colony in the Ukraine. The “brethren,” as they called themselves, met regularly in homes for Bible study and prayer. These home Bible studies were the cradle for the birth of the Mennonite Brethren Church. Two developments brought about a break with the old church.

First, several small groups of the brethren (which also included sisters) requested a sympathetic elder of the Mennonite church serve them the Lord’s Supper in their own home, according to Acts 2:46-47. They wanted to celebrate communion more frequently, but their request was also a reaction to taking communion with people who had made no open profession of faith. The elder refused their request on the basis that private communion was without historical precedent, would foster spiritual pride and could cause disunity in the church. In November of 1859 the brethren decided to take the Lord’s Supper in a home without the elders’ sanction.

Second, church meetings were held to decide how to discipline the renegade revivalists. It appeared that reconciliation would be possible. Unfortunately a few unsympathetic opponents verbally attacked the leaders of the house Bible study movement. Eventually about 25 members were lost to the house church movement.

On Epiphany, January 6, 1860, a group of brethren met in a home for a “brotherhood” meeting. This gathering proved to be the charter meeting of the Mennonite Brethren Church. Those present examined a letter of secession that explained their differences with the mother church. The letter affirmed their agreement with the teaching of Menno Simons and addressed abuses they saw in baptism, the Lord’s Supper, church discipline, pastoral leadership and lifestyle. Eighteen men signed the document. Within two weeks an additional nine men signed the letter of secession. Since each signature stood for a household, the charter membership of the Mennonite Brethren Church consisted of more than 50 people.

Core Theology

At this point we can identify several distinctive Mennonite Brethren emphases true to the early MB Church as well as today.

- The need for systematic Bible teaching is primary. Rejection of lifeless formalism leads to joyous expression, but this must be directed by thorough biblical instruction.

- There is a keen need for spiritual discernment since religious ferment is subject to powerful emotional expression with shallow intellectual consideration. Emotion and personal experience are servants not masters; obedience borne of biblical study is to be our guide.

- Leadership is to be entrusted to members with integrity and spiritual balance.

- While strong and wise leaders are needed, dictatorship is suspect and to be rejected. Congregational participation and action are necessary for a strong church polity.

- A strong ethical emphasis is needed. Happiness divorced from holiness leads to false freedom. Faith and practice must be kept in proper balance.

- Meaningful church worship is essential. Lukewarm worship opens the door to hyper-emotional expressions. Radical renewal demands appropriate worship forms.

The Mennonite Brethren Church in Russia grew rapidly. By 1872, 12 years after its founding, the Mennonite Brethren church numbered about 600 members. The group held its first formal meeting, and it was a time of inspirational meetings and planning for evangelistic church extension. Participation in foreign missions began with financial support of mission societies, and the first MB mission field established in India.

Migrations to North America

When the Russian government introduced universal military service and for economic reasons, some 18,000 Mennonites migrated from Russia to North America from 1874 to 1880. Among the immigrants were many Mennonite Brethren.

The new settlers experienced all the hardships of pioneer life, including primitive sod houses, grasshopper plagues, lack of markets for their produce and limited educational opportunities.

In 1878, the first interstate meeting of Mennonite Brethren leaders was held near Henderson, Nebraska. The primary issue was uniting Mennonite Brethren congregations for mission purposes. This interest in evangelism and mission has continued to bind Mennonite Brethren congregations together through the years.

By the turn of the century, Mennonite Brethren congregations had been established in Kansas, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Oklahoma, Colorado, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, and soon after in California, Montana, Texas, Oregon and Washington. They worked together as the General Conference of MB Churches, a binational body that was organized into four regional districts.

Reorganizing North America ministries

In 1954, North American Mennonite Brethren reorganized into two national conferences, while retaining the General Conference to oversee foreign missions, seminary education, publications and historical preservation. Church growth and evangelism, youth work, Christian education concerns, stewardship and Bible and liberal arts colleges became the responsibility of the national conferences.

In 1960 the Krimmer Mennonite Brethren Conference merged with the U.S. Conference, adding nine congregations in the Midwest and several in North Carolina that were the result of KMB evangelistic mission efforts in the Appalachian mountains of western North Carolina. Today seven congregations, six of which are primarily African American, comprise the North Carolina District Conference.

In 2000, Canadian and U.S. Mennonite Brethren voted to divest the General Conference ministries to the two national conferences. The two national conferences continued to work together as owners of MB Biblical Seminary and MBMS International, now known as MB Mission.

In 2010, ownership of MB Biblical Seminary-Fresno was transferred to Fresno Pacific University, the Mennonite Brethren denominational university owned by the Pacific District Conference, ending joint ownership of the denomination’s seminary.

U.S. and Canadian Conference leaders continue to meet regularly to consider ministry opportunities in North America and to support one another.

U.S. Mennonite Brethren Today

Since the U.S. Conference was established in 1954, it has grown beyond its original European beginnings. Today half of our 200-plus congregations worship Sunday mornings in a language other than English. Much of this diversity can be attributed to a visionary plan known as Mission USA when it was introduced in 1988.

The Mission USA strategy included four components: a vision for unity, a vision for renewal and resourcing, a vision for leadership training and, most significantly, a vision for mission “within and across cultural lines.” The intent was to reach beyond traditional boundaries and backgrounds in national church planting efforts and to plant 60 new churches by the year 2000, with 30 of those congregations being among the many immigrants coming to the United States.

By 1996 the focus of Mission USA narrowed to church planting and church health primarily among English-language people while a new ministry, Integrated Ministries, was responsible for planting and integrating immigrant congregations. By 2000, 42 immigrant congregations were active members of the U.S. Conference.

Church planting under Mission USA was successful and continued until 2016 when MB Mission began exploring the possibility of partnering with C2C Network, the church planting ministry of the Canadian Conference of MB Churches, to expand MB Mission's work beyond global ministry to include local and national ministry efforts as well.

The shift in church planting coincided with a two-year review of U.S. Conference mission and strategy that began in 2014. The review involved a cross-section of local, district and national U.S. Conference leaders and culminated in a document known as the Future Story that was released at the 2016 U.S. Conference National Convention.

The new vision focuses on three core commitments: church multiplication and evangelism, intentional disciple-making and leadership development. The strategy emphasizes networking and helping to empower each local congregation to reach its full, God-given potential within the framework of our evangelical and Anabaptist distinctives.

In the 21st century, the U.S. Conference, now referred to as USMB, grew thanks for church planting efforts. But in late 2017, a group of 10 congregations previously affiliated with Mennonite Church USA, joined the Central District Conference and USMB.

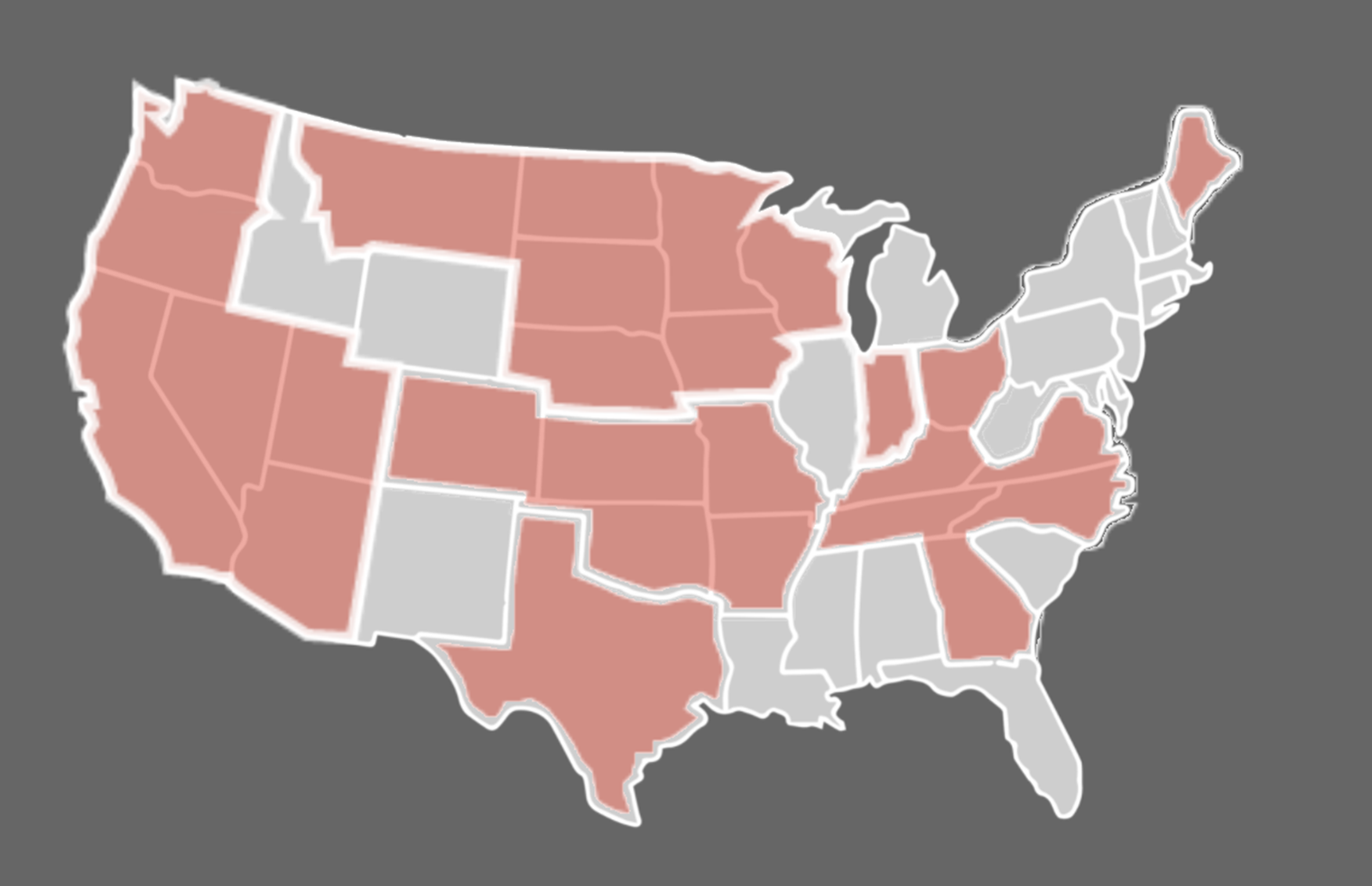

This brings to 26 the number of states that are home to USMB congregations. USMB congregations are located in Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, Wisconsin, Iowa, Indiana, North Dakota and South Dakota (Central District Conference); Arizona, California, Oregon, Utah, Nevada and Washington (Pacific District Conference); in Texas (Latin American District Conference); in Arkansas, Kansas, Oklahoma, Colorado and Missouri (Southern District Conference); in Kentucky, Maine, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee and Virginia (Eastern District Conference); and in Georgia.

Although methods have changed, U.S. Mennonite Brethren remain committed to bringing people into the Kingdom of God and nurturing them as disciples of Christ Jesus. Our story continues to unfold as we follow God’s leading and seek to make disciples of all people.

We have a full-length and short version of the MB Story video available in .mp4 format upon request. Please email offices@usmb.org for more information.

Find a Church